Gordon Bell Special Prize

A crowning achievement: Simulations of how the Coronavirus spike protein opens

Terra Sztain1, Surl-Hee Ahn1, Anthony Bogetti2, Lorenzo Casalino1, Zied Gaieb1, Fiona Kearns1, J. Andrew McCammon1, Jason McLellan3, Lillian Chong2, Rommie E. Amaro1

- University of California at San Diego

- University of Pittsburgh

- University of Texas at Austin

We are proud to have been a part of an incredible team effort to simulate the coronavirus in atomic-level detail (a simulation containing millions of atoms!), which won the 2020 Gordon Bell Special Prize in HPC-based COVID-19 Research (see our video). This massive effort was the culmination of only 6 months of work from 28 scientists across the country from 10 different institutions. Due to the global emergency of the pandemic, an unprecedented amount of computing power was made available for these efforts, including resources at four supercomputing centers. link pdf

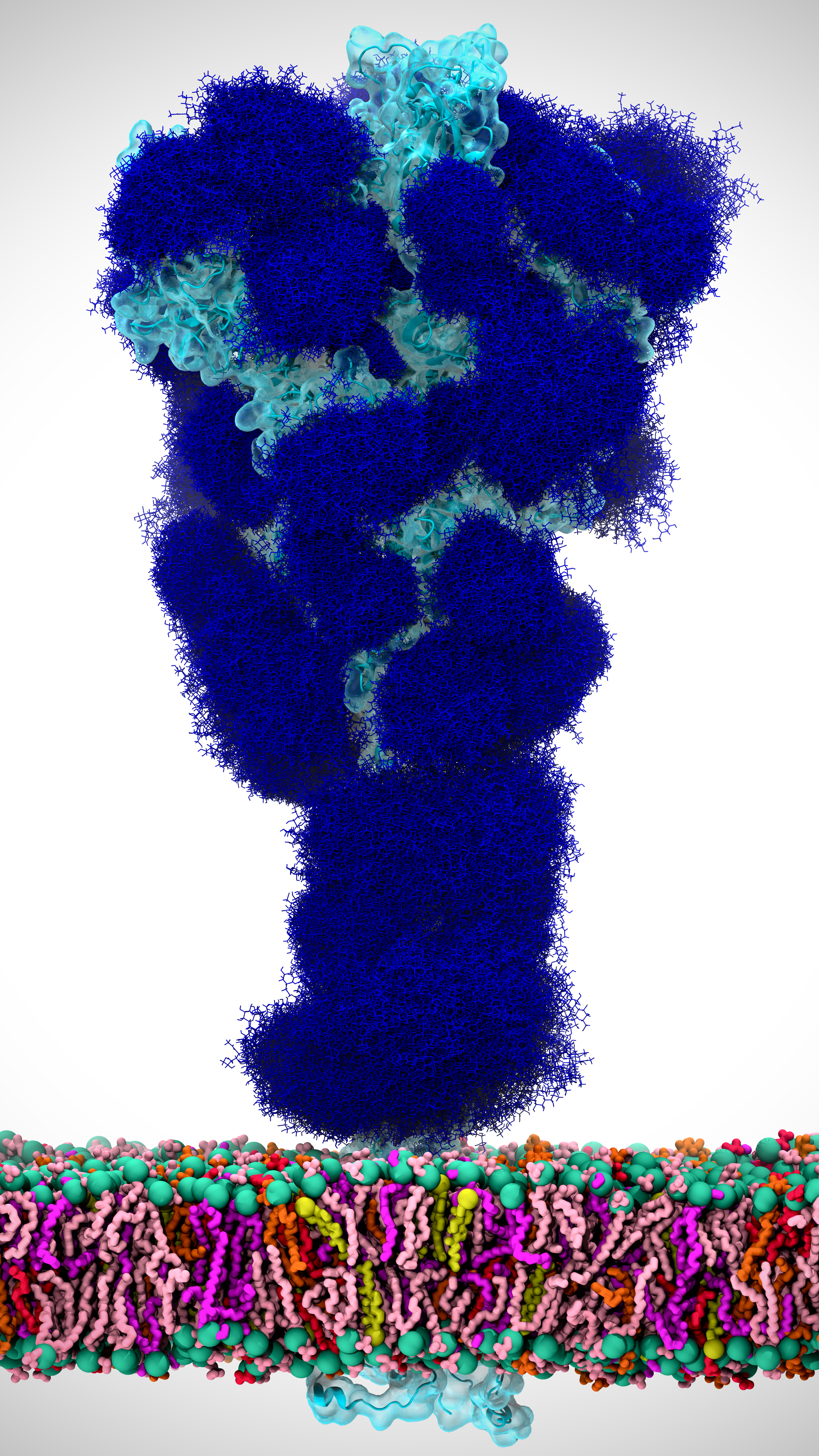

Figure 1. The coronavirus spike protein, which protrudes from the virus surface as shown above, is the virus’ first line of attack. A detailed understanding of how the spike protein opens up and latches onto host cells can help turn the tide in the fight against the virus. Our simulations of the spike protein were in the absense of the viral membrane. Image created by Lorenzo Casalino.

A crowning achievement of our effort was the generation of atomically detailed views of how the coronavirus’ spike protein (Figure 1) opens up, an essential motion of the virus’ most deadly and infectious tool. Standard simulations of this opening process for such a large protein (~600,000 atoms) would have taken years, even when using state-of-the-art computer hardware and many, many GPUs. This is a lower-bound, ball-park estimate, assuming that the spike opening is on the microsecond to millisecond timescale.

Figure 2. The problem with standard simulations (blue spheres) in sampling long-timescale processes such as the opening of the spike protein is that most of the time is spent “waiting” in the initial stable state for a “lucky” transition over the free energy barrier.1 However, these transitions are relatively fast once they occur. To more efficiently simulate these interesting, functional transitions, the weighted ensemble strategy focuses the computing power on the actual transitions rather than the stable states themselves.

We simulated coronavirus spike opening using the weighted ensemble strategy.2,3,4 By focusing computing power on the transitions between stable states (Figure 2), the weighted ensemble strategy can be orders of magnitude more efficient than standard simulations in generating unbiased, continuous pathways and rate constants for rare events (e.g., large-scale protein conformational transitions and protein binding). In addition, the strategy can be applied to any stochastic process2,3 and a target state does not need to be strictly defined in advance.5

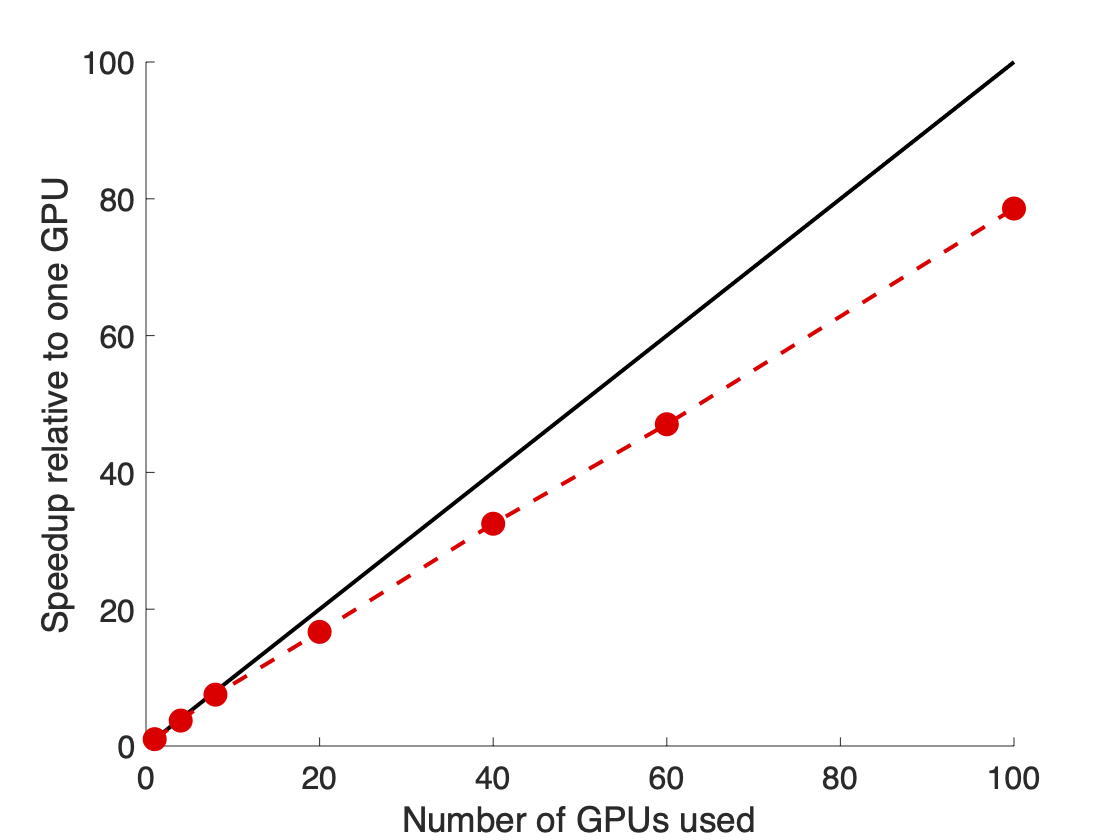

To run our weighted ensemble simulations, we used the open-source WESTPA software6 which scales out to a large number of GPUs (as well as CPU cores) (Figure 3) and is interoperable with any dynamics engine of choice. In our simulations, we used the GPU-accelerated Amber dynamics engine, which gave a 16-fold speedup in dynamics propagation on a GPU vs. CPU.

Figure 3. The WESTPA software scaled almost linearly on 100 NVIDIA V100 GPUs on the Longhorn supercomputer. This scaling enabled the fast and efficient simulation of the coronavirus spike opening.

In only 23 days, our WE simulations generated 204 continuous pathways of spike opening to the open state and 106 continuous pathways of spike opening to a newly discovered “super-open” state. These trajectories reaching the “super-open” state passed through a state which aligns well with cryoEM structures of ACE2 bound spikes.

Finally, our WE simulation has provided a high-quality training set of spike opening pathways for the Deep Drive MD efforts by Arvind Ramanathan and co-workers to characterize the opening process in the context of a much larger system that includes cellular membranes.

We are excited to see how so many different simulation techniques could be integrated to meet the grave challenge that humanity currently faces. We look forward to what the weighted ensemble strategy can tackle next, and how our recent results can help stop the coronavirus!

References

- Zwier, M. C. & Chong, L. T. Reaching biological timescales with all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. Current Opinion in Pharmacology vol. 10 745–752 (2010).

- Huber, G. A. & Kim, S. Weighted-ensemble Brownian dynamics simulations for protein association reactions. Biophysical Journal vol. 70 97–110 (1996).

- Zhang, B. W., Jasnow, D. & Zuckerman, D. M. The ‘weighted ensemble’ path sampling method is statistically exact for a broad class of stochastic processes and binning procedures. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 054107 (2010).

- Zuckerman, D. M. & Chong, L. T. Weighted Ensemble Simulation: Review of Methodology, Applications, and Software. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 46, 43–57 (2017).

- Suárez, E. et al. Simultaneous Computation of Dynamical and Equilibrium Information Using a Weighted Ensemble of Trajectories. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 10, 2658–2667 (2014).

- Zwier, M. C. et al. WESTPA: an interoperable, highly scalable software package for weighted ensemble simulation and analysis. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 800–809 (2015).